Should Your Retirement Portfolio Withdrawals Vary With the Market?

We delve into the trade-offs associated with flexible withdrawal systems versus those that deliver steady cash flows.

Research we released a few weeks ago came to an uncomfortable conclusion: Retirees who want to live on a predictable stream of income yet maintain a high level of certainty around not running out would do well to keep their spending down. Rather than the 4.0% that is often cited as a safe initial withdrawal rate, our research suggests that a 3.3% starting withdrawal amount is likely to be sustainable for balanced portfolios over a 30-year time horizon. (Here's the full paper.)

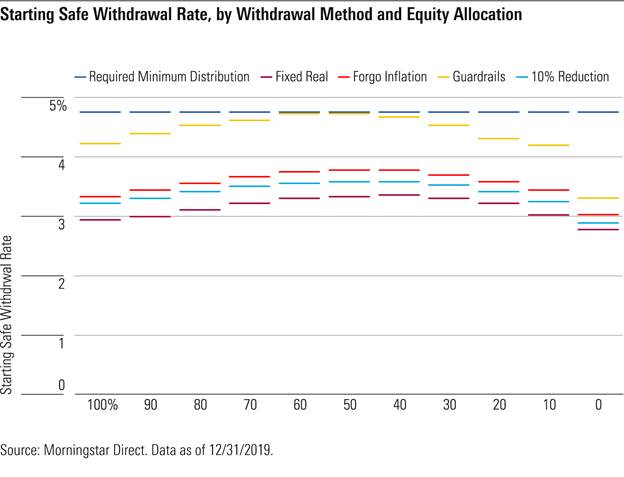

That's sobering, but we also found that even modest tweaks to the withdrawal system can help elevate starting withdrawal amounts. For example, taking fixed real withdrawals but simply forgoing an inflation adjustment following a losing portfolio year resulted in a 3.76% starting withdrawal rate for a balanced portfolio. Meanwhile, truly flexible strategies such as the guardrails strategy, developed by financial planner Jonathan Guyton and computer scientist William Klinger, can lift starting and lifetime withdrawals even more meaningfully. By cutting back on withdrawals in down markets but allowing retirees periodic raises in good ones, the guardrails method supported a starting safe withdrawal rate of 4.72%--above the 4% guideline. The exhibit below depicts starting safe withdrawal rates for the various withdrawal systems we tested in the paper. "Fixed real" in the exhibit refers to someone using a 4%-style system--taking X% in year one of retirement, then inflation-adjusting the withdrawal amount. You can see that all of the variable methods we tested provided a little--or a lot--of lift to that baseline withdrawal system.

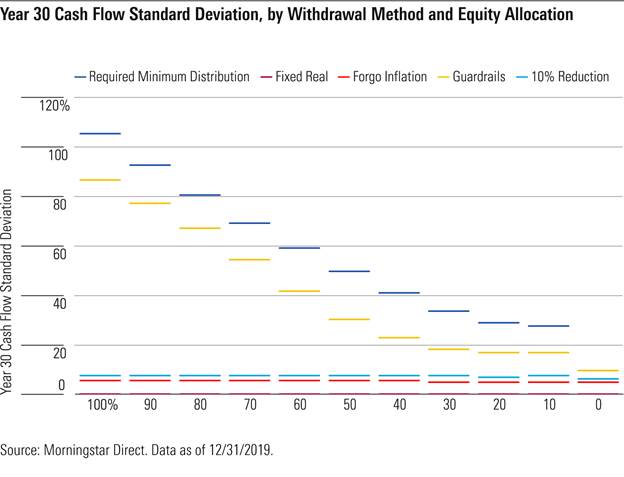

But while flexible systems may elevate withdrawals over a retiree's lifecycle, they can also lead to undesirable volatility in household cash flows. In short, they may not be very livable. The next exhibit shows that some of the same withdrawal systems that delivered the highest starting safe withdrawal rates led to higher cash flow volatility on a year-to-year basis during the drawdown period.

Additionally, variable systems like the guardrails system tend to be more efficient, increasing withdrawals in up markets and ensuring that the retiree consumes more of his or her portfolio along the way. From that standpoint, such variable systems tend to be more appropriate for so-called "last breath, last dollar" retirees and less appropriate for bequest-minded ones.

In the end, the "right" withdrawal method is highly dependent on the retiree's personal situation: level of wealth, stability of preretirement income, and desire for certainty about not running out of money, among other factors. Here are some of the key considerations to bear in mind when determining the appropriate withdrawal system.

Age/Remaining Life Expectancy

Younger: More-Flexible Withdrawals

Older: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

One of the key risks for retirement is sequence of return risk, which is the risk of encountering a weak market environment in the early part of retirement, when the portfolio is at its highest level. It is less of a risk factor if a retiree encounters such a market environment later in retirement, after making it through the danger zone of the first 10 to 15 years, with the portfolio needing to last for a shorter period of time. For that reason, a variable withdrawal system will tend to be most appropriate for new retirees and may be less necessary for people who have been retired for many years. Indeed, the Guyton-Klinger guardrails method relaxes its withdrawal rules after the first 15 years. That argues for new retirees varying their withdrawals, whereas older retirees will need to worry less about tethering their withdrawals to their portfolios' performance.

Market Environment

High Equity Valuations and/or Low Bond Yields: More-Flexible Withdrawals

Low Equity Valuations and/or High Bond Yields: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

In a related vein, expectations of market returns can also influence whether a retiree employs a variable strategy or opts for fixed real dollar withdrawals. A fixed real dollar method is not inherently problematic if a retiree embarks on retirement in a period of low bond yields and/or high equity valuations. But if these factors also lead to lower market returns, the starting withdrawal amount that is then inflation-adjusted throughout retirement might need to be uncomfortably low. Employing a flexible withdrawal system helps address the above-mentioned sequence of return risk while also allowing for the possibility of higher withdrawals during times when the market environment is more rewarding.

Level of Wealth

More Wealth: More-Flexible Withdrawals

Less Wealth: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

A key factor in whether a given withdrawal system is "livable" is a retiree's level of wealth and the extent to which changes in the withdrawal rate might be a small nuisance or begin to have a significant impact on the retiree's quality of life. It is a good bet (though by no means a certainty) that a 25% reduction in spending would have a bigger negative impact on the quality of life for the retiree who goes to $45,000 from $60,000 than it would for the retiree who needs to drop to $150,000 from $200,000. Because the dollar amounts are so much smaller, there is not as much room to cut nondiscretionary expenses.

Coverage for Fixed Expenses From Nonportfolio Income Sources

More Coverage: More-Flexible Withdrawals

Less Coverage: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

In a related vein, the extent to which a retiree is meeting basic living expenses--housing, food, utilities, and healthcare, for example--from nonportfolio sources is also a factor. The retiree who covers most of such expenses using income from sources like Social Security, a pension, rental income, or an annuity will be better situated to absorb variations in portfolio cash flows than would the one who is relying more heavily on the portfolio to cover basic needs.

Variability of Income While Working

More-Variable Income Stream: More-Flexible Withdrawals

More-Stable Income Stream: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

The retiree's own earnings pattern while working is also apt to influence one's comfort level with varying portfolio withdrawals based on performance. The retiree who experienced very stable cash flows from work--for example, a teacher whose income received an automatic inflation adjustment--may be less comfortable with portfolio cash flows that vary from year to year. Meanwhile, retirees who experienced lumpy income streams while working--commissioned salespeople or business owners, for example--might be more willing to vary their cash flows in retirement, too. (Of course, it is perfectly plausible they may prefer more-stable cash flows, too.)

Desire to Maximize Lifetime Spending

Strong Desire to Maximize Lifetime Spending: More-Flexible Withdrawals

Less Desire to Maximize Lifetime Spending: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

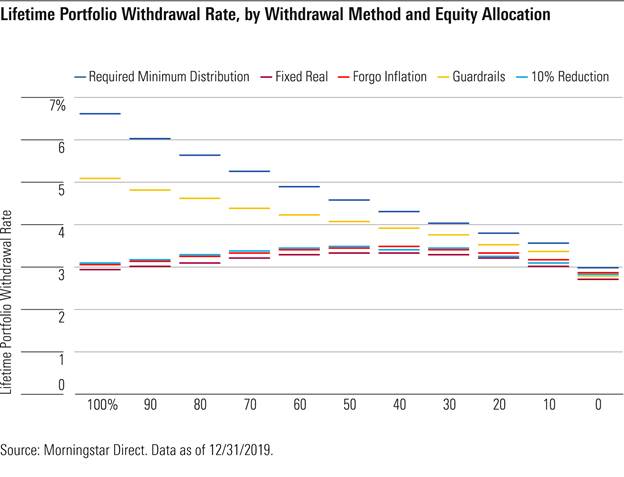

While a system of fixed real withdrawals runs the risk of premature asset depletion if the initial withdrawal amount is too high, it also runs the risk of underspending if the initial withdrawal rate is too low and/or the market performs well over the retiree's time horizon. Retirees who employ flexible withdrawal systems, by contrast, will be able to employ course corrections on an ongoing basis, thereby deriving greater utility from their portfolios during their own lifetimes. Variable strategies inherently court less of a risk of inadvertently leaving substantial assets behind and help maximize lifetime withdrawals. As the exhibit below illustrates, variable systems like the guardrails and required minimum distribution methods help maximize lifetime withdrawals relative to more static withdrawal systems. That's especially true for portfolios with higher equity allocations: The higher equity allocation helps lift the portfolio's prospective return.

Bequest Motive

Strong Bequest Motive: Less-Flexible Withdrawals

No/Weak Bequest Motive: More-Flexible Withdrawals

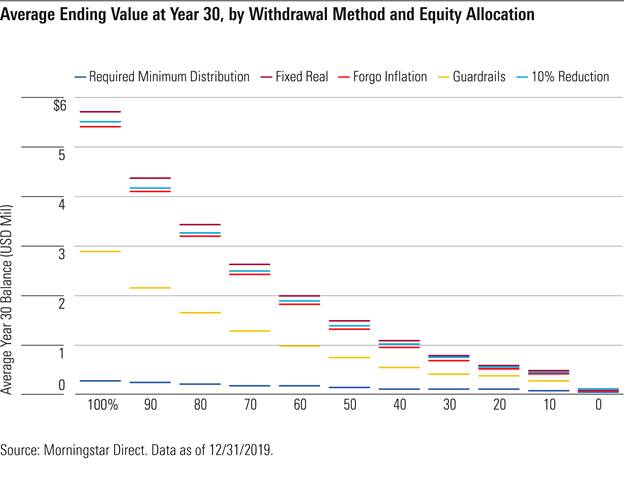

Our research demonstrates that a fixed real withdrawal system tended to lead to higher ending balances than did more flexible systems like the guardrails and RMD methods. (The exhibit below illustrates the ending balances for the various withdrawal systems and asset allocations that we tested.)

That is because flexible methods give retirees a "raise" when their portfolios have done well, meaning that they consume more of their portfolios on an ongoing basis than is the case with a fixed real withdrawal system. However, it is worth noting that retirees using any of the withdrawal systems could ensure a bequest by segregating the bequest assets from spendable assets. That two-part system would allow the retiree to maximize lifetime withdrawals while also ensuring that the bequest assets remain untouched.

Desired Certainty About Not Running Out

Mixed

No withdrawal system perfectly alleviates the risk of prematurely running out of funds. But provided the starting withdrawal amount was low enough, the fixed real withdrawal system tended to contribute to higher ending balances than did variable systems. That's because, in contrast with variable withdrawal systems, fixed real withdrawal systems don't offer the opportunity for raises when the portfolio performs better than expected. By offering higher average balances after 30 years, fixed real systems provide more of a buffer against an unexpectedly long life than would be the case with variable systems.

On the other hand, variable strategies inherently allow the retiree to adjust to market conditions as well as expectations about life expectancy in a way that fixed real systems do not. By allowing retirees to make those course corrections, variable systems offer more control than fixed real withdrawal systems, and therefore might impart greater peace of mind.